I left a bratty comment on my friend’s Facebook page the other day. She posted a picture of a T-shirt poking fun at Tourette Syndrome (I won’t include the text, since it’s just downright cruel, but curious readers will have no trouble finding it on Google). I commented, “Tourette Syndrome is a real condition that real people suffer from.”

I’m sure I caught her off guard, because she knows I love to swear. Swearing’s my favorite! We got to talking, with her apologizing for offending me, and me apologizing for being a brat. The thing is, once upon a time, I might have clicked “Like” on that post. But that was before I had my own Tourette Syndrome scare.

A couple of years ago, when my son was about three and a half, he developed a strange little quirk. At the end of almost every sentence he uttered, he’d repeat the last few words in a whisper. Something like, “Can I please have some juice? (have some juice.)” My husband and I let it slide for a while. Then, he started repeating the ends of our sentences, too: “Go clean your room.” “(Your room.)” We’d ask him why he was doing it, and he looked at us like we had three heads. He didn’t even realize he was doing it.

Finally, I Googled “whisper repeating” and came up with the real terms for his quirk: palilalia refers to the repetition of one’s own words, and echolalia refers to the repetition of other people’s words, or other sounds. Both conditions are often indicators of autism or Tourette Syndrome.

I know what you’re thinking. It’s never a good idea to get your medical information from the internet. But we all do it anyway (at least, I hope it’s not just me). And nowhere on the internet could I find any indication that otherwise neurotypical children suffered from palilalia or echolalia. I was terrified. We made the first available appointment with our pediatrician. Meanwhile, we kept a close eye on the boy, cataloging other possible tics (at this point, we were no longer calling them “quirks”).

Sometimes, when he was engrossed in a book, game, or TV shows, he’d softly say “uh.” Was that a tic? How long had he been doing that? Other times, he’d open his mouth really wide for no reason. What was that about? Was that normal? We didn’t say anything to him about the tics, just whispered to each other and silently wrote them down on a notepad. When possible, we surreptitiously recorded video of him on our phones.

We learned that there are two types of tics a person can have. Motor tics are physical movements, such as making faces, shrugging, or blinking repeatedly. Vocal tics include making short sounds like “um,” grunting, or throat-clearing. More severe vocal tics include echolalia, palilalia, and coprolalia, the tic that comes to mind when we hear the word Tourette Syndrome -- shouting obscene words or phrases. It’s important to note that fewer than 10% of all tic sufferers actually display coprolalia. But it’s the most dramatic tic, so of course it gets the most attention.

The day of the doctor’s appointment came, and I presented my findings to the doctor. I noticed that the tics often occurred when I was reading to my son, particularly if it was a new book that he was unfamiliar with, so I had the doctor observe while I read to him. The doctor took it all in, and then calmly let me know that in the 15 minutes we’d been there, he’d observed all the tics I’d listed for him, plus a few more. All told, my son had about 10 tics, both vocal and motor.

That’s when I lost it. I never wanted my son to see me cry. I never wanted his doctor to see me cry. But right then, here’s what I heard: “Your son is going to be considered a freak. It doesn’t matter how funny he is. It doesn’t matter how handsome he is, how smart, how friendly. Everyone will only see him as freak that does weird things. He will disrupt classes at school. All the kids will make fun of him. Hell, even the teachers will make fun of him behind his back. He will never have any friends. He will come home crying every day, because the other children will torment him for doing something that he can’t help. Something he doesn’t even realize he’s doing. His life will be filled with pain and misery. You can try drugging him, but it probably won’t help.”

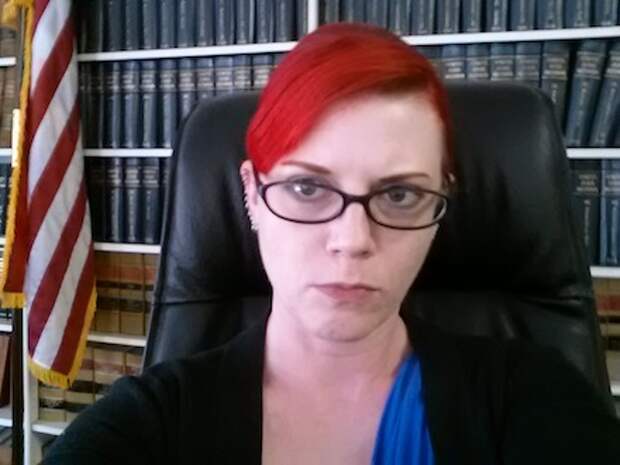

What the doctor actually said, was that tics are very common in children his age, and most kids outgrow them. He said that he had no reason to think that he was autistic, but due to the unusually high number of different tics that he had, Tourette Syndrome was an outside possibility. He referred us to a neurologist. Luckily, while my mind was going crazy, and my face was struggling to keep the tears and sobs inside, my right hand was scribbling furiously in my notepad, writing down everything the doctor said, so I could read it later, when I was a little more rational (thanks, hand).

We’re very lucky to live near Boston, home to some of the best hospitals and doctors in the world. Within a couple of weeks, we got in to see a pediatric neurology team at Boston Children’s Hospital. My husband took the day off from work. I bought my son a new book to read in front of the neurologists. They reviewed the notes from his pediatrician. They listened to our stories. They watched the videos and observed my son in action. And they said he was fine.

Fine? Really? I think I asked them “Are you sure?” about twenty times. He had a lot of tics, true, but it wasn’t Tourette Syndrome. Just a lot of tics. Like our pediatrician had told me, they are common in young children, and they had every reason to believe that he would outgrow them.

Tics are often brought on by stress or anxiety, and my husband realized that we had been going a little heavy on the workbooks lately. So we backed off. For a couple of weeks, I didn’t do anything educational with him whatsoever, just to give him a break. When I started up again, I tried to focus more on “unschooling” than a traditional approach.

After a few months, I realized that my son hadn’t displayed any tics in…I don’t know how long. I mentioned it to my husband. He’d noticed, too. Now, whenever he approaches a big milestone (such as learning to read or ride a bike), he’ll start up with the palilalia again. And that’s when I know to back off. I’m confident that eventually, he’ll be completely tic-free.

And I will never laugh at another Tourette Syndrome joke again.